*** BELLE CORA BLOG ***

by Joe Bonadio, North Beach resident and writer

joecontent.net/blog

Always Clever: SF Invented The Martini, The Jukebox And The TV

Across the world, modern day San Francisco has a reputation for creativity and invention. We’ve earned the credit: our tech giants have become the dynamo of the American economy, and our unorthodox, fertile business environment incubates many of the world’s most successful and innovative companies.

And this tendency toward innovation is anything but a recent trend. They say that in New York, the emphasis is on the new, but the Big Apple has nothing on San Francisco when it comes to world-changing innovations. Today we’re going to look at three that most people will find pretty familiar: the Martini, the jukebox and the television.

The Martini - The Occidental Hotel, Montgomery Street

The Martini: a simple cocktail of gin and dry vermouth, garnished with an olive or a twist of lemon. The drink is such a staple of bar culture, it’s hard to imagine a world without them. And while there are a lot of stories surrounding the birth of this most iconic of cocktails, the most persistent all seem to pit the bartenders at San Francisco’s Occidental Hotel against those of an anonymous saloon in Martinez.

The gist of the story is this: in the mid-1800’s, a lucky miner fresh from the Sierra Nevadas rolled into nearby Martinez, CA for a little celebration. Gold dust burning a hole in his pocket, he knocked the dirt from his clothes and demanded champagne. There being no bubbly in the house, the bartender got creative and shook up (or was it stirred?) a brand-new cocktail: gin, with a splash of white wine.

San Francisco's Occidental Hotel

Not quite a martini, but the good doctors at the Occidental Hotel bar would fix that. When the miner took the recipe back to San Francisco with him, they went to work on it, substituting vermouth for the vino. Et voila! The Martini was born, named for Martinez, the town that inspired it.

Alas, the Occidental, once the playground of Mark Twain and a surfeit of other notables, is now gone, destroyed in the earthquake and fire of 1906. The Martini lives on, just one more reminder to the world at large: all the best things come from San Francisco.

The Jukebox - Le Palais Royal, 303 Sutter Street

There is nothing quite so American as a jukebox, but most of us never stop to think where they originated. San Francisco is the answer, specifically the Palais Royal Saloon. Not to be confused with the Palais Royal in the first arrondissement of Paris, or the $159 Million obscenity of a beach house in Florida, Palais Royal was a gin mill. And unlike the jukebox, it’s long gone now.

Palais-Royal in Paris, France. Not The Birthplace Of The Jukebox.

But in 1890, San Francisco inventors Louis Glass and William S. Arnold chose the place to debut their brand-new invention. It wasn’t called a jukebox at first; that moniker didn’t appear until the 1930s. Instead, they called their device the “nickel-in-the-slot player:” An Edison Class M phonograph fitted with four “eartubes" that transmitted sound, it wasn’t amplified, so only four people could listen to a track at a time (listeners were thoughtfully supplied with towels to wipe off the tubes for the next user).

Rocking Out At The Palais Royal Saloon (photo: Bettmann/Corbis)

Patented under the name Coin ActuatedAttachment for Phonograph, the contraption was an immediate success, reportedly earning over $1,000 in its first six months of use. In time the invention prompted scores of imitators, and jukeboxes eventually became ubiquitous in drinking establishments across the country. Jukeboxes were actually a key source of income for music publishers, and at one point in the 1940s, three-quarters of the records produced in the U.S. winded up in jukeboxes.

Alas, the advent of portable radios and cassette decks spelled doom for the jukebox industry, and today there are only two companies still producing them (Rock-ola is one of them). But they remain an enduring part of 20th Century Americana (and notably, they are still one of the defining traits of the Classic Dive Bar).

The Television - Philo Farnsworth’s Lab at 202 Green Street

The charms of North Beach are beyond number, and the neighborhood has always played a big part in the story of San Francisco. But few realize that our perfect little corner of the universe also gave birth to one of the most influential electronic gizmos the world has ever seen: the modern television.

In September of 1927, Philo Farnsworth transmitted the first image with his “image dissector camera tube” at his laboratory on North Beach’s Green Street. Less than a year later he was demonstrating a working model to the San Francisco press. Television had become a reality.

Of course, it would be 1936 before the first public broadcast, and in the intervening years, there was a lot of work for the attorneys. A fellow named Vladimir Zworykin had been experimenting with the cathode ray tube while working for Westinghouse Electric; it seems he had an overlapping patent claim that went back to 1923. RCA ended up owning that patent, and they did everything they could to wrest control of the technology away from Farnsworth. After being frustrated in the courts, RCA finally agreed to pay Farnsworth $1 million and licensing fees, and went forward with their plans to develop the technology for the commercial market.

For good or bad, the subsequent rise of TV transformed the world in so many ways, it’s probably impossible to estimate the impact. The advent of television advertising in 1941 was the true birth of the American consumer market, and the adoption of the home video screen paved the way for a class of devices that would still be evolving over a century later.

Whatever your thoughts on the matter, one thing is certain: the whole thing started just three blocks away on Telegraph Hill.

Movies We Love: North Beach On The Big Screen, Part 1

As photogenic as our fair city is, San Francisco has always held a natural appeal for filmmakers. A brainier, more temperate alternative to the glitz of Hollywood, the Bay Area has been a northern sanctuary for movie types for decades. Many of them have chosen to shoot here in North Beach, and its hardly a surprise: with its italianate character and winding, picturesque alleyways, the place is like one big movie set. For your viewing pleasure, here are just a few of our favorite films featuring scenes of North Beach and Telegraph Hill. We'll start with one of the most famous films in movie history...

Vertigo

Of all the movies featuring scenes of North Beach, the most iconic is Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), starring Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak. Considered by many to be the best thriller ever made, the film was shot all over the city, but Hitchcock’s choice of locations shows the director’s particular fondness for North Beach. Case in point: legendary hotspot Ernie’s Restaurant, which until 1995 occupied 847 Montgomery just below Broadway, was immortalized in the film. Four scenes were filmed there, and Hitchcock had both the interior and exterior meticulously reconstructed on a soundstage in Hollywood to allow for panorama shots the restaurant didn’t permit.

The Exterior Of Ernie's Restaurant, Carefully Reconstructed On A Soundstage In Hollywood

Hitchcock was a devoted fan of the restaurant, especially their selection of first-growth bordeaux, and dined there regularly when he was in San Francisco–which was often. He even cast the actual bartender and maître’ d’ as themselves in the picture, flying them to Hollywood to film, where they had the rare chance to mingle with the celebrity cast.

The film’s most recognizable shot of our corner of the city wasn’t filmed at Ernie’s, however. That honor goes to the memorable sequence filmed at 900 Lombard Street atop Russian Hill. Before you protest and say that isn’t North Beach, take a closer look at the photo below. In the scene, Madeleine (Novak) has just arrived at Scotty’s apartment (Stewart) to leave him a thank you note for saving her after she chucked herself in the bay at Fort Point. As she climbs out of her Green Jaguar, she is unaware that she has been followed (ok, it’s a long story–we recommend it). Point being, in the background of the shot you can see another star: Telegraph Hill’s very own Coit Tower.

Madeleine (Kim Novak) Visits The Neighborhood In Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo

Hitchcock apparently intended our beloved landmark as a phallic symbol, one of several erotic symbols he worked into the background of Vertigo’s sets. And ours isn’t the only tower highlighted in the film–the nearby Ferry Building tower makes a few proud appearances as well.

Bullitt

When speaking of classic San Francisco cinema, another name that frequently comes up is Steve McQueen. His epic chase sequence in Peter Yates’ Bullitt (1968) set the standard for movie car chases for years to come, and McQueen’s classic green '68 Mustang GT is one of the most famous automobiles in movie history.

Steve McQueen and Jacqueline Bisset During The Filming Of Bullitt (courtesy of http://neoretro.tumblr.com)

Interestingly, the oddest thing about the celebrated chase is only apparent to locals and others who know the city: geographically, the thing doesn't make a bit of a sense. Continuity was evidently thrown by the wayside for the sake of visual appeal, and at points the action jumps abruptly from Potrero Hill to Russian Hill and from North Beach back to Potrero Hill again, in a ride that bears little similarity to reality. It does look good on film, though.

Steve McQueen Lights Them Up Somewhere In SF. What Is It With The Green Cars?

Another thing few people know: the chase was originally supposed to continue across the Golden Gate Bridge, but apparently the city would have none of it. And contrary to popular belief, McQueen did little of the breakneck driving captured in the film. He was a red-hot Hollywood property at the time, and the studio couldn't take the chance; stuntman Loren James was actually behind the wheel for 90% of the shots. For more details on the shoot from the man himself, click here.

Dirty Harry

While we’re on the subject of tough guys, North Beach has played host to more than one macho movie icon over the years. With Dirty Harry (1971), Clint Eastwood created a character that will be forever lodged in the cranium of American pop culture. Harry Callahan was gruff, no-nonsense, and well-armed with an envy-inducing .44 magnum, a certain breed of Hollywood antihero. Explosively violent, but typically stoic until time came for the perfect line, he claims one of the most famous in cinema history in this film: ‘You've got to ask yourself one question. Do I feel lucky? Well, do ya, punk?’

From Arnold Schwarzenegger to Bruce Willis, action heroes have been ripping this guy off forever.

Dirty Harry Callahan (Clint Eastwood) Explains His Nuanced Views Of Law Enforcement

What many forget is that one of the key scenes in Dirty Harry was filmed (or shot, I suppose) right in the middle of North Beach. The scene starts with Saints Peter and Paul Church, the camera panning south across the park to the Dante Building where ‘Scorpio,’ the movie’s main perp, is perched with a sniper’s rifle. The scene concludes with a rooftop-to-rooftop shootout, but Scorpio escapes and continues to menace the public until finally being dispatched by Callahan at the end of the film.

Unlike Steve McQueen, Eastwood did all of his own stunts in the film, including one in which he jumps from a bridge on to the roof of a moving bus. And though the Callahan character (loosely based on David Toschi, chief investigator on the Zodiac Killer case) is considered by many to be Eastwood’s signature role, he was anything but the first choice. The part was first offered to a half-dozen other leading men, including John Wayne, Frank Sinatra….and Steve McQueen.

The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill

Lest you think North Beach cinema short on sensitivity, we’ll conclude this list with Judy Levin’s The Wild Parrots of Telegraph Hill (2003). An award-winning documentary, it focuses on the relationship between a local flock of wild parrots and a bohemian musician living in a cabin on Telegraph Hill (Mark Bittner, who wrote the book of the same name). A deeply personal film, it’s a love letter to our corner of San Francisco, with too many breathtaking shots to count.

Writer Mark Bittner, Subject Of The Wild Parrots Of Telegraph Hill, On Set With A Couple Of His Costars

Levin is a longtime resident of Telegraph Hill, and the film is gorgeous, and steeped in her affection for the neighborhood. As she follows the life of this unusual, thoughtful man, she manages to capture the place’s essence, arguably as well as any film ever made. And if you like a good surprise ending, you’re in for a serious treat. In fact, you can watch it free here.

This article is part of a series examining the fascinating people and places that make up the rich history of North Beach and The Barbary Coast. Visit us again soon for more.

Cheese & Fire: The Rustic Wonders of Raclette

For true lovers of cheese, there is one traditional dish that is impossible to match: Raclette. At Belle Cora, we are huge fans of what the Swiss once called bratchäs, or “roasted cheese.” And now that we are serving it every Monday night, we thought we’d give our guests a little background on this delicious specialty.

Indigenous to parts of Switzerland, raclette is a semi-hard cow’s milk cheese, usually made in large rounds. In the traditional preparation, the center of the round is heated until it is bubbly and slightly browning, then scraped onto the serving plate. The word raclette actually comes from the French racler, meaning to scrape, and this was originally done in front of an open fire. Today, it’s typically accomplished with an electric tabletop device built for the purpose.

Raclette Prepared The Old-Fashioned Way, Directly Next To The Flames

Served with fresh bread alongside a toothsome combination of small potatoes, pickled onions, gherkins, and cured meat, raclette is the quintessential Swiss comfort food. If you’ve never tried it, you’re in for a rare treat; there is nothing more enticing than the smell of roasting cheese as it fills up the room on a Winter evening. And when it finally hits your plate, the tangy, gooey raclette is everything you expect, perfectly balanced by the accoutrements.

Raclette is generally paired with a white wine like a riesling or pinot gris, served only semi-cool to aid digestion. The Swiss have historically advised against drinking water with the dish, as it can ‘harden the cheese’ in your stomach (a likely story). Whatever the case, we particularly enjoy it with a nice glass of our Gruner Veltliner.

The history of Raclette goes back over 700 years, the dish originating with peasants in the Swiss Alps who would carry the cheese rounds along with them into the mountains as they herded cows, and heat them up next to the campfire at night to scrape on to their bread. The practice has survived over the centuries, and thankfully you don’t have to go through any of that. Just come by Mondays between 6:30 and 10:00, bring your appetite, and we’ll take care of the rest. Full plates go for $18, and you can have yours without meat for $15.

The Swiss Alps: Not Surprisingly, They Go Better With Cheese

The point of raclette is an extended, relaxed dining experience with friends, where the quality of the company and conversation is matched only by that of the food and wine. We love it, because that’s what Belle Cora is all about, too.

And we’d be remiss if we didn’t mention our other Winter favorite: flown in directly from Munich, our Bavarian pretzels are warm and soft, and served with cheese sauce and two kinds of mustard. Go big, and get one with a perfect, sizzling bratwurst to pair with your choice from our draft menu. Prost!

We’ll look forward to seeing you soon. And don’t forget we were recently granted our Limited Live permit, meaning we’re now presenting live music on a regular basis. Happy February!

Mark your calendars-

RACLETTE MONDAYS: Every Monday from 6:30-10:00 pm

Napa Uncorked: The Judgment of Paris

California’s position in the wine world is so firmly established today, it’s difficult to imagine a time when it could have been otherwise. In truth, you don’t have to go very far back in our history to find a California whose wine industry was just getting its bearings: specifically, just before the now-legendary Judgment of Paris.

A wine competition organized in May of 1976 by English wine merchant Steven Spurrier (no, not the football coach), the contest pitted the best California wines in two categories (chardonnay and cabernet sauvignon) against their French equivalents in a blind tasting. At the time, French wines were widely considered to be far superior to those vinted in California, but the pedigreed judges (all of whom were French) gave the win to California in both categories. For the reds, honors went to Stag’s Leap ’73 SLV Cabernet; Château Montelena’s ’73 Chardonnay was the victorious white.

Steven Spurrier, organizer of the Judgment of Paris tastings, in 2011

Outside of a few lines in Time Magazine, the affair initially received scant attention, and it was largely ignored by the French press. When it was mentioned across the Atlantic at all, it was in a tone of utter ridicule; the reputation of French wines was ironclad, and most Europeans considered the results a fluke. The sensitivity of France was particularly understandable: most of the French competitors came from the ’70 vintage, judged by Conseil Interprofessionel du Vin de Bordeaux to be among France’s best of the previous half-century.

When it was further suggested that the California wines would never hold up to their French counterparts over time, a rematch was clearly in order. In a second blind tasting held at the Vintner’s Club in San Francisco almost 2 years after the Paris event, the California wines actually improved their standing, nabbing all three top spots for both chardonnay and cabernet. There have been a number of re-tastings over the years (of the reds, the whites being past their prime), yielding similar results. Amazingly, the upstart Californians had not only bested their French elders out of the gate, their wines appeared to be aging better as well.

Meanwhile, all of this attention was having a tremendous effect on the California wine industry. At the time of original Paris tasting, there were less than 70 wineries in Napa. Today there are at least six times that many, depending how you count. Mike Grgich, the winemaker who created the winning chardonnay for Château Montelena, broke ground on Grgich Estates the following year. Though he went on to become a legend in the winemaking community, at the time Grgich was just another young winemaker among many, throwing his hat into the ring behind the optimism of the Judgment of Paris. After 1976, Napa would never be the same.

Legendary winemaker Mike Grgich poses at the estate on his 90th birthday

Interestingly, none of this was Spurrier’s plan. His livelihood was French wines, and the wine merchant arranged the event with the full expectation that the near-mythical French estates would crush the fledgling California vintners. Though he had tasted a few California wines, he didn’t have access to the best of them in London, and actually purchased the wines for the competition (two bottles of each) on a trip to California with his wife. (As you can imagine, Spurrier's well-intentioned efforts didn’t exactly endear him to French vintners, and at one point he was barred from participating in France’s prestigious wine tasting tour circuit for an entire year.)

But the story wasn’t over, and indeed, the best was yet to come. In a grand 30th Anniversary tasting event (again arranged by Spurrier, and held in London and Napa simultaneously), a prestigious panel of 18 judges judged the now 30+ year-old wines once again. Many French (and francophiles) were convinced their wines would finally prevail after three decades of bottle aging. The results were stunning: the California wines completely dominated, claiming all five top spots. Napa was exultant.

The winning wines:

1971 Ridge Vineyards Monte Bello

1973 Stag's Leap Wine Cellars

1971 Mayacamas Vineyards (3rd Place tie)

1970 Heitz Wine Cellars 'Martha's Vineyard' (3rd Place tie)

1972 Clos Du Val Winery

In retrospect, this is a very impressive roster of wines; that these wineries were largely unknown as late as 1976 is difficult to fathom today. And if you look more closely at the results, there was yet another upset to be found: Ridge Vineyards of the Santa Cruz Mountains had only placed fifth in ’76, but when the wines were tasted thirty years later, it stole first place. Just like Napa Valley, sometimes it takes a little while to show your true potential.

The otherworldly Château Montelena in Calistoga

The Judgment of Paris just celebrated its 40th anniversary last year, and over the decades has taken on a mythical quality, especially here in Northern California. The 2008 Hollywood comedy “Bottle Shock” was loosely inspired by its events, and another film, this one based on George Taber's 2005 book “The Judgment of Paris,” is now in production (Taber was the original Time reporter in 1976). Today, the two original winning bottles are on display at the Smithsonian Museum.

Winter Solstice: A Farewell To 2016

By Joe Bonadio

The week between Christmas and New Year’s Day is unlike any other. For many of us, it comes as a welcome respite from our daily schedules, a much-needed pause in the routine. It’s also a chance to draw a breath and reflect as we prepare for the new year ahead.

Most of the December holidays derive from the solstice: the day on which the sun dips to its lowest point in the sky, and the shortest day of the calendar year (this year, the solstice fell on December 21st). This has always been an important holiday because it symbolized so much to our ancestors. The solstice ceremonies were a celebration of life, held just before the descent into Winter; for our distant relatives it was a season fraught with peril, and many didn’t survive until springtime.

Plunging into 2017 at Belle Cora

As I was walking to work this morning, my gaze fell for the hundredth time on the massive work-in-progress that is the Salesforce Tower. Once complete, the structure will be the tallest in San Francisco, a miracle of design and engineering. But this morning, like every other time I’ve looked at it, the construction site seemed utterly still. There is undoubtedly a flurry of work going on down there; skyscrapers clearly don’t build themselves. But from a distance, no movement can be detected.

It has to be said: its high points notwithstanding, 2016 has been a trying year, for a host of reasons. And it seems like many of us in San Francisco are closing it out with a slight sense of....unease. To me, it almost feels as if people are holding their collective breath before plunging into 2017.

The Salesforce Tower Nears Completion South of Market

Our ancestors were smart. We know that, because we are here today, living proof of their viability. They celebrated the solstice because they knew what was important, and that there was a time for everything: to plant, to harvest, to rest–and to party. I won’t pretend that we don’t have a lot of work ahead of us. But just like our ancestors, we have each other to count on. And in the meanwhile, we’ve got the rest of the weekend to party.

Things move slowly in this system, sometimes so slowly that you can’t see them move at all. And sometimes it may even seem as if they are moving backwards. But the work gets done; the towers rise, more or less on schedule. As we toast each other this week, let’s keep that in mind, and remember just how fortunate we all are. It’s a long way to Spring, but together we’re going to get there.

Thank you all for reading the blog, and for making Belle Cora a big part of your year. Here's to a very Happy New Year, and I look forward to seeing you at the bar!

Vagabonds, Lunatics and Scoundrels in San Francisco History, Part 3

If there is one neighborhood that has set the tone for San Francisco and cemented its reputation for rebelliousness, it had to be the Barbary Coast. The environ we now call North Beach has had an enduring influence on the city’s development, and still does today. San Francisco’s no-holds-barred Barbary Coast origins still reverberate here and throughout the city, expressed in the innovation and boundless sense of possibility SF has come to be associated with in the modern age.

But as the city has learned, this anarchic spirit has its dark side. With license comes the licentious, and the annals of San Francisco are replete with the widest variety of reprobates, rapscallions and social outliers that any American city has ever seen. To document these noteworthy ne’er-do-wells, today we bring you the third edition of Vagabonds, Lunatics And Scoundrels in San Francisco History.

Tessie Wall

We’ll start back in the 19th Century, with the notorious and colorful madam Tessie Wall. Raised in San Francisco’s Mission District, Tessie was born in 1869, and by all accounts led a normal childhood. A comely and curvaceous young woman, she married early, supporting herself and an errant, alcoholic husband with her job as a housekeeper. But when she lost her first child to respiratory illness within months of his birth, the marriage foundered, and Tessie's path was forever altered.

The only surviving image of Tessie Wall

Her work in upper class homes had exposed her to the prurient predilections of her wealthy benefactors, and Tessie quickly found a way to put them to use. Once free of her husband, she purchased a bordello in the Tenderloin, and hired a coterie of young girls to staff her first venture. Business was brisk at Wall’s sumptuously appointed ‘parlor house,’ and she soon opened a second location. Her clubs were immensely popular among the city’s elite, and frequented by many of the society people whose homes Tessie used to clean.

Tessie was a natural promoter. She would secure the latest fashions straight from Paris and New York, adorning her ladies in them and staging parades on Market Street that dramatically increased business. She was also celebrated as a prodigious drinker, and once bested legendary boxer John L. Sullivan in a champagne marathon–after 21 glasses of the bubbly, the heavyweight champ was on the floor at Tessie’s feet.

But of all her notable features, it was her wild, romantic heart that secured Tessie’s enduring place in San Francisco history. Like many in her profession, she had a keen craving for social acceptance, and chose to marry a politician–prominent Republican Frank Daroux–who was also a club owner. But Daroux’s business was gambling, a vice that at the time didn’t interfere with his political career. Brothels were another matter though, and Daroux made no small effort to get his wife to leave the business. He even built her a house in the country at one point, but Tessie was headstrong to say the least, remarking that she would rather “be an electric light pole on Powell Street than own all the land in the sticks.”

The couple fought constantly, and the tempestuous marriage came to an end when Tessie learned that Daroux had betrayed her with another woman. Distraught, she followed him to the theater, where she confirmed what she had heard; seeing her husband with a strange woman on his arm was more than Tessie could bear. She waited in the shadows outside the theatre until he emerged and stepped onto the sidewalk, lighting a cigar. So deep was his reverie that he didn’t hear his wife’s approach. Tessie fired her revolver point blank into his chest, and as he fell backward, fired twice more.

When the police arrived, Tessie was kneeling over her husband, weeping, the empty pistol in her hand. Asked why she had shot him, Tessie cried “I shot him ‘cause I love him, goddamn him!” Daroux survived, though his political career did not. Remarkably, although Tessie also tried to shoot his mistress through a café window soon afterward, neither ended up pressing charges. Tessie Wall returned to the bordello business, and died 16 years later at the age of 63–from an impacted tooth.

Owsley Stanley

Now we jump forward to the Summer of Love, a period not so much chronicled as mythologized by writers and the press in the decades since. In 1967, San Francisco was teeming with all things new, and extreme personalities and fabulous oddballs were the order of the day–along with plenty of psychedelic drugs. LSD was the elixir of choice, the X-factor, and it had its share of prominent champions, people like Timothy Leary, Ken Kesey–and Owsley Stanley.

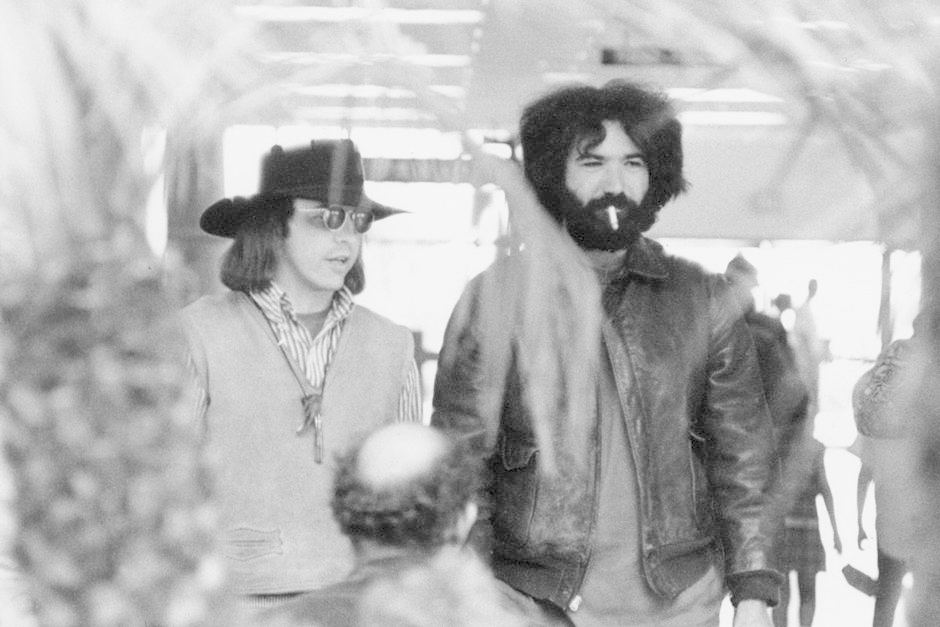

The early manager and financier of the Grateful Dead, Owsley was responsible for creating the laboratory-grade LSD that helped define the late Sixties counterculture. He was reportedly the first to ever mass-produce the drug, in a bathtub near the Berkeley campus (a process he mastered during a marathon 3-week session at the university library).

Owsley with Jerry Garcia in 1969 (photo: Rosie McGee via Reuters)

It’s hard to overstate Owsley’s impact during this period: his legendarily pure blotter powered Ken Kesey and the Merry Prankster’s famed Acid Tests, and Owsley is said to have turned both Jimi Hendrix and John Lennon on to the drug. Lennon reportedly contracted for a lifetime supply of Owsley’s LSD, said to have been a major influence on the Beatle's Magical Mystery Tour album and film.

Early on, Owsley had all the earmarks of a people’s pharmacist; he was thrown out of military prep school in the ninth grade for supplying alcohol to his classmates for Homecoming. In the Air Force he learned electronics, a skill set he would later use to perfect the Grateful Dead’s celebrated “Wall of Sound” live sound system. His association with the band lasted well into the 70’s, and he recorded nearly every show the Dead played during this period; Owsley was even behind the band’s iconic “Steal Your Face” skull-and-lightning-bolt logo.

The Dead's 'Steal Your Face' Logo, Designed By Owsley Stanley

Nicknamed “The Bear” for his hairiness (quite a distinction in San Francisco at the time), Owsley was at the very center of the psychedelic scene here, and is said to have produced as many as five million doses of his signature LSD. He served two years in prison for narcotics possession, and led a reclusive life in his later years, relocating to the bush country in Australia. Owsley was immortalized by several popular songs in the 70’s, including Steely Dan’s “Kid Charlemagne,” but the ultimate tribute may have come from the Oxford English Dictionary, which defines Owsley as

An extremely potent, high-quality type of LSD; a tablet of this. Frequently attributive, especially as Owsley acid.

Jim & Artie Mitchell

As the city credited with launching the Sexual Revolution, San Francisco has always had more than its share of pornographers. But none had quite the impact of a pair of quarrelsome brothers from the East Bay: Jim and Artie Mitchell.

In 1969, the brothers renovated a dilapidated building on a Tenderloin street corner and opened what would be their first of 11 adult cinemas: the now legendary O’Farrell Theatre. From this humble start the brothers would build a multimillion dollar adult entertainment business that continues to this day.

Artie (right) and Jim Mitchell in 1977 (photo courtesy of Associated Press)

They revolutionized the porn trade, and were the first to transfer erotic films to video tape and market them through adult magazines. The money they made was arguably as obscene as their output, and they quickly became fixtures on the San Francisco scene. Their Tenderloin sex emporium became a déclassé gathering spot for a certain contingent of celebrities, including the band Aerosmith, Hunter S. Thompson and journalist and local gadfly Warren Hinckle.

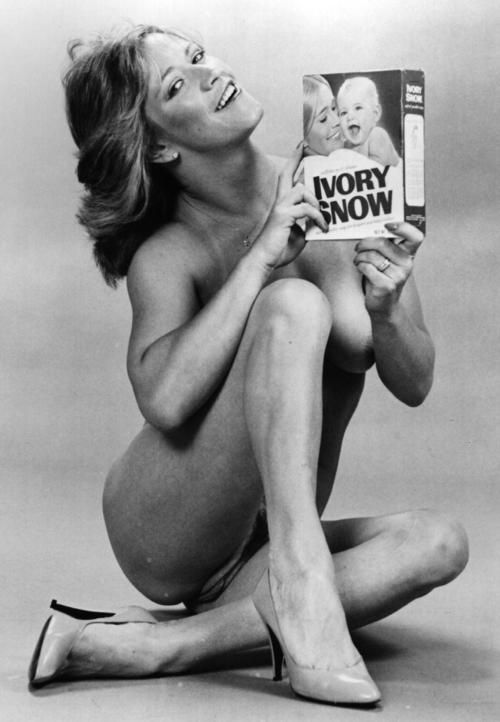

Their first taste of national notoriety came when they produced “Behind The Green Door,” featuring Marilyn Chambers, then a new arrival to the adult film scene. Soon after the film’s release, it was revealed that Ms. Chambers was the same woman currently adorning the front of the Ivory Snow detergent box on store shelves across the nation. Though it was pure chance, no advertising agency had ever concocted a more devious publicity stunt, and sales of the film went through the roof. Produced for around $60,000, Green Door went on to gross over $25 million. The Mitchell Brothers porn empire had been born.

Marilyn Chambers Poses With The Now-Legendary Ivory Snow Box

With money flying in the door at an increasing rate, business acumen fell by the wayside. The brothers hired high school friends to help manage things, who reportedly spent much of their office hours drinking, drugging and shooting pool. At the center of the disorder was Artie Mitchell, whose cocaine and alcohol abuse had become so bad that friends begged Jim to intervene. On February 27, 1991, Jim drove to Artie’s home, armed with a .22 rifle he inherited from their father. The two argued, and Jim drew the rifle and shot his brother and longtime business partner dead. After a long trial, Jim Mitchell was prosecuted for voluntary manslaughter, and was released from San Quentin after serving only 3 years.

On July 12, 2007, Mitchell passed away at his ranch house in Sonoma, the victim of heart failure. His funeral was attended by former District Attorney Terence Hallinan, Mayor Willie Brown and some 300 others. Jim Mitchell was interred at Cherokee Memorial Park in Lodi, California, in the plot next to his brother Artie.

Years later, tragedy struck the family again when Jim’s son Jim Mitchell was arrested for the Novato murder of his ex-girlfriend. The mother of his year-old daughter, Danielle Keller was bludgeoned to death by Mitchell with a baseball bat on her front lawn. During his trial, the partial heir to the Mitchell Brothers business and fortune claimed he was railroaded by the press and courts, and simply the victim of his ‘notorious’ Mitchell name. The jury wasn’t buying, and the younger Mitchell was sentenced to 35 years in prison.

North Beach Echoes: Music Venues We Miss

Among its manifold charms, North Beach has one of the richest musical traditions of any neighborhood in America. In the popular imagination, North Beach and jazz are nearly synonymous, and it’s not hard to see why: from the long-forgotten Anxious Asp to the legendary Keystone Korner, this patch of land has hosted a phalanx of serious music venues. And the music hasn’t all been jazz–far from it.

But like all else, music clubs pass on. It’s sad to watch them go, and this little neighborhood has lost more stages than most cities will ever have. But they are like mushrooms in the cool, damp air: others always appear. Today we’ll take a glimpse back, and remember a few music establishments that North Beach will always miss.

Jazz Workshop - 473 Broadway

We’ll start the tour on Broadway, at the famed Jazz Workshop. One of the focal points for jazz on the West Coast during the genre’s heyday in the 60’s, it was opened on Broadway in 1958 by lawyer Art Auerbach. Immortalized by the many ‘Live at the Jazz Workshop’ recordings made there, the club inherited the all-star roster of downtown’s Blackhawk when it closed in 1963, and played host to a who’s who of jazz greats: Bird, Monk, Miles, Dizzy, Coltrane and dozens more.

Miles On The Marquee At The Jazz Workshop On Broadway (photo courtesy of theconcertdatabase.com)

Cannonball Adderley was a regular headliner at the club, and was so popular that crowds would line the sidewalk to hear him work the saxophone. Charlie Mingus also frequented the Jazz Workshop’s stage, and was known for his aggressive, unpredictable performances. Between his groundbreaking original numbers, he was known to abandon his bass to crack a bullwhip over the heads of his alarmed audience.

And the club had more than great jazz on tap. Lenny Bruce is said to have perfected his comedy act there and at the Hungry I across the street, and on October 4, 1961, he was arrested at the Jazz Workshop, the first of Bruce’s arrests for obscenity. The circumstances seem nearly quaint now: the comic had used the word co@&sucker to refer to the patrons of a nearby bar, and then done a relatively innocuous bit about the term “to come” (though the case ended in acquittal, it’s difficult to believe this was enough to get you arrested in San Francisco in 1961).

Lenny Bruce Is Booked After Being Arrested At The Jazz Workshop In North Beach, San Francisco

Jazz Workshop foundered at the beginning of the 70s, and though other incarnations of the club came and went for years, its stature as a jazz mecca never returned. As the tumultuous decade of the 60’s came to an end, that mantle had passed to another establishment, just one block north: Keystone Korner.

Keystone Korner - 750 Vallejo Street

A 200-seat club just a few steps away from Central Station on Vallejo Street, Keystone Korner originally opened as a topless bar in 1969; the name was chosen as a jibe to the “Keystone Kops” next door. Owner Freddie Herrera (whose wife was the club’s only dancer) was soon convinced by friends that music was a better play than topless, and decided to change things up. He began booking local rock musicians, and did well enough to open another Keystone in Berkeley. Just three years later, the North Beach location was purchased for $12,500 by Todd Barkan, who shifted the emphasis to jazz.

The Legendary Keystone Korner, Steps Away From Central Police Station On Vallejo Street

Rock had largely replaced jazz as America's genre of choice at this point, and many of the jazz venues in the neighborhood had perished (or become topless clubs themselves). Regardless, Barkan’s decision proved a fortuitous pivot: just as Jazz Workshop had in the decade before, Keystone Korner quickly attracted the biggest names in the business. Sonny Rollins, Miles Davis, McCoy Tyner, Dexter Gordon, Bill Evans and Stan Getz all performed at Keystone Korner, and the club rapidly grew into one of the best jazz clubs in America. The place was a favorite of many of the musicians who played there, and at the time Getz singled it out as “the number one jazz club in the world today.”

The club always struggled financially, but creatively it was a powerhouse, and Barkan was an infectiously enthusiastic ringleader, well-liked by his peers. When the business teetered, the community rallied behind the place, and benefits were periodically held to keep it afloat. In spite of the club’s fiscal troubles, everyone who worked there shared Barkan’s commitment to the place, and it fostered a loving, supportive atmosphere in which the musicians shined. Keystone Korner lasted eleven years under Barkan, and over the course of that time hosted hundreds of live recordings, many of which have have become parts of the jazz canon.

In 1983, Barkan appeared in an article on the front page of USA Today’s entertainment section naming the top three jazz clubs in America, his club among them. Ironically, Keystone Korner had just closed its doors.

The Anxious Asp - 528 Green Street

All but forgotten now, The Anxious Asp warrants a mention for its location alone - right across the street from Belle Cora, in the space now occupied by Tattoo Boogaloo. Popular with the beats in the Sixties (Kerouac read his poetry there), the Asp’s jukebox purportedly held the largest collection of Charlie Parker records west of the Mississippi River, and the bathroom walls were papered with pages from the Kinsey report.

The Asp was Janis Joplin’s favorite spot when she hung out in North Beach, and Jimi Hendrix is said to have habituated the place as well. Apparently Janis (this was before she became famous) was fond of singing along to the jukebox, so much so that annoyed regulars would yell at her to stop, and she was once beaten up out front by a couple of equally unappreciative bikers.

Some accounts say it was a lesbian bar, some call it a bohemian haunt, but one thing is certain: everyone was welcome at the Anxious Asp. Alas, the club finished its run in late 1967.

Mabuhay Gardens - 435 Broadway

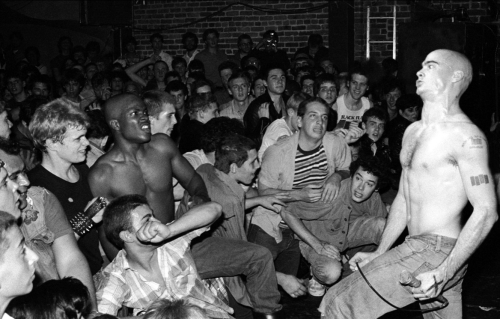

Of all the venues to ever grace North Beach, perhaps the most notorious of them all was Mabuhay Gardens. A Filipino restaurant and nightclub that started booking punk bands in 1976, Mabuhay Gardens (AKA the Mab, or the Fab Mab) is now regarded as one of the most important clubs of the punk movement, and played host to every major band in the genre. Black Flag, Blondie, Devo, the Ramones – name virtually any punk band, and they played on this stage at least once.

A Dancer Revs It Up At Mabuhay Gardens

Mabuhay’s location on Broadway (right next door to the spot inhabited by the Jazz Workshop a few years earlier) naturally brought in the topless dancers who worked the clubs nearby. Most nights, the resulting crowd was an odd marriage of punkers, strippers and curiosity seekers. Along with host Dirk Dirksen’s vitriolic emceeing style (he routinely insulted performers and audience members alike) it made for an atmosphere thick with tension and sexual energy. The place quickly became ground zero for punk rock on the West Coast, San Francisco’s emphatic answer to New York’s CBGB.

Dirk Dirksen, Irascible Impresario Of North Beach's Legendary Mabuhay Gardens (photo courtesy Jeff Good)

Dirksen was undoubtedly an effective promoter, but his true gift was his singular presence onstage. With his dog (named Dummy) under his arm, he would deride and provoke his audiences until they cursed and threw things at him, then bang – on with the next band. It was an odd formula that somehow worked, and led to the frenzied, anarchic crowd participation that the club became famous for.

Jello Biafra Of The Dead Kennedys Conjures Chaos: The Band Played Its Debut Show At The Mab

Variously referred to as the “pope of punk” and the "poor man's Bill Graham,” Dirksen earned the honorifics, and had an extraordinary impact on punk music. By personally creating an exchange program for bands in London and New York so they could play here, he helped transform punk rock, a once-underground movement, into the global phenomenon it became.

Henry Rollins Of Black Flag Gets Weird At The Mabuhay Gardens, 1981 (photo courtesy henryrollins-org.tumblr.com)

Unfortunately, no one could duplicate Dirksen’s acerbic, confrontational style, and once he stepped away the club declined, closing in 1986. Two years after Dirksen passed in 2006, the cross street where the Mabuhay Gardens once raged was rechristened Dirk Dirksen Place.

North Beach Icon: The Saints Peter And Paul Church

Towering over the streets and alleyways of North Beach, the dignified spires of the Saints Peter and Paul Church are a defining element of our storied neighborhood. They keep faithful watch over Washington Square, the state’s oldest park, like aging sentinels, imbuing the square with a palpable sense of history. Along with the clanging of the cable cars and the mournful sounding of foghorns in the bay, the church bells are an integral part of our unique aural landscape, keeping us ever mindful of the special place we inhabit.

Completed in 1924, the church replaced the original Saints Peter and Paul Church on the corner of Filbert Street and Grant Avenue (then Dupont Street), which burned to the ground in the earthquake of 1906. Over the last century, it has become one of San Francisco’s most iconic neighborhood landmarks, and along with Coit Tower, the church has come to signify North Beach for legions of visitors.

The Steeples Of The Saints Peter And Paul Church

I recently had the chance to tour the church with my friend David Burbank, who has worked as Sacristan of the property for the last decade. On the day of our appointment it was mid-Fleet Week, and the roar of military aircraft was in the air as I negotiated the short walk from my apartment: the Blue Angels rehearsing their big show for the weekend.

I was very curious about the church's history, excited for the tour–and just a tad nervous. I haven’t attended church regularly since my early teens, and this would be my first trip in years. As we climb the steps to enter the church, the sky above the park is torn by the earsplitting sound of a diving $60 million jet fighter–a suitably dramatic entrance. Looking over my shoulder, I can see the pilots’ contrails, and they form a perfect cross in the sky. Even better.

A Celestial Greeting From The Blue Angels

David launches right into his subject, practically bouncing on his toes. The statue directly above the entrance (which I’ve walked by obliviously a thousand times) is an important relic: the oldest known sculpture of St. Vincent de Paul, a French Roman Catholic priest canonized in 1737. Called the “great apostle of charity,” St. Vincent de Paul dedicated himself to the needs of the poor, and the sculpture is the only piece of statuary that survived the fire at the church’s original location.

The Oldest Known Surviving Statue of Saint Vincent de Paul

Once we’re inside, David runs down some stats for us, and it’s impressive to say the least: The church seats 720 worshippers, and employs five priests and one brother. The steeples rise 191 feet above the square, and the height of the nave is a soaring 60 feet. The church contains 138 stained glass windows, all of which were made here by Italian glaziers brought to San Francisco expressly for that purpose (they also created the glass for the chandeliers). The elaborate altar was wrought from Carrara marble in Italy, and weighs 125 tons; it was brought here on a ship as ballast, and took an entire year to make the trip around Cape Horn, arriving in 1926.

To take advantage of the tax-free status for places of worship, the top two floors of the structure were built as a parochial school, u-shaped and surrounding the interior of the church below like a horseshoe. The school serves grades pre-K through 8, and currently has 238 students. The kids have to deal with a lot of stairs, but it’s a truly rarefied setting for a school, and the classroom windows command spectacular views of both the city and the Bay below.

The High Altar, Erected In 1926

Standing at the altar, it’s easy to become lost in the richness of detail. It seems no corner has been cut anywhere, an impression reinforced when we step around to the back of the altar and see that the elaborately carved marble work continues, even into the church workspace. An immense painting of Jesus Christ, rendered by Ettore and Giuditta Serbaroli in 1949, decorates the dome above the altar; backstage, we now view it from below, framed by struts and supports. The open book in Jesus’ left hand displays the Latin words “Ego sum via, veritas et vita,” meaning “I am the way, the truth and the life.” The letters that surround him are Greek: IC, XC and NK, the first and last letters of the Greek words for “Jesus Christ conquers.”

Ettore & Giuditta Serbaroli's Painting Of Jesus Christ, A Modern Version Of Christo Pantocrator, As Seen From Behind The High Altar

In the slightly cramped office behind the altar, I notice an image of Jesus on an 8 ½” x 11” sheet of paper, scotch-taped to the wall. “Strikes me as a bit of overkill,” I whisper to my companion. After a moment, she notices it and laughs, drawing a glance from our dependable Sacristan.

Of course, overkill is an unfamiliar concept to those who build Catholic churches. Everywhere you rest your eyes you see impeccable handiwork, all evidence of incalculable amounts of talent, time and effort expended. And like the 24-karat gold leaf adorning an alarming amount of the cathedral’s surface area, none of this comes cheap: The original investment in the cathedral and school was $800,000, and though you can’t get a 2-bedroom apartment for that now, it was a princely sum in the twenties. Today’s upkeep costs, meanwhile, are truly astronomical: when the rebar in the towers was reinforced a few years back, the cost of the job was over $2.5 million.

The Keyboard Of The Majestic Pipe Organ

Next stop: the immense pipe organ, which sits in the fore of the church. Built by Schoenstein & Co. of San Francisco in 1987, it has over 1,800 pipes divided into thirty ranks. It sits beneath the Rose Window, an exquisite 14’ stained glass window that represents the lamb before the throne of God, placed just above the church's entrance. The afternoon sun slants through the brightly colored panes, casting a serene, amber glow over the space. David tells us how stained glass is made: different colors of glass are ground to a fine dust, and baked into a “canvas” pane–one color at a time. It’s painstaking, tedious work, and in this case the results are sublime. The colors and shading are as subtle as painted work, and if you look closely you can see the brushstrokes of the artists, long since past.

A Detail Of The Rose Window: The Twelve Angels Around The Periphery Symbolize The Twelve Apostles And Twelve Tribes Of Israel

Remembering my days as a novice Catholic, I ask David about the confessionals. I learn the church has six of them–elaborately appointed, of course–three on each side of the nave. But they don’t see a lot of action these days: apparently, today’s parishioners prefer to confess their sins one on one. If you‘re feeling old-school, though, you can still go the anonymous route on Saturday afternoons between 4:00 and 5:00.

The Awe-Inspiring Nave Of Saints Peter And Paul Church

We head next to the sacristy, the space where the priests and attendants prepare for services, and where vestments, sacred vessels and other church furnishings are stored. This is David’s domain. He points out the prominent stained glass portrait of Don Bosco, the founder of the Salesian order and spiritual father of the church. Because the beloved priest wasn’t yet a saint when the church was built, it had to be placed inside the sacristy, rather than in the church proper–and the portrait is sans-halo. David also points out the curious blue sink that stands near the exit: called a piscina, it is used to wash linens and purificators (cloths that clean out holy vessels) used during mass. To prevent sacred items such as baptismal water from being swept into the sewers, the sink drain (called a sacrarium) flows directly into the ground.

The Piscina

As we mount the age-worn stairs, it feels as if the tour is building to a climax. A quick turn around the school reveals a different world entirely; aside from the fact that it sits atop a 92-year-old church, this is a small primary school like any other. We meet the principal, a personable woman named Lisa Harris (Dr. Harris, as I learn from the school’s website), and I experience a vague wish that I could have gone to school in this lovely, cloistered place.

Emerging into the sunlight on the roof of the church, we are expecting a grandiose view, but are nonetheless gobsmacked. It is a glorious Indian Summer day, and North Beach and the bay beyond stretch away to the horizon. The sky is crisscrossed with the trails of the F-18s roaring overhead, and the city below glitters and beckons in the afternoon light. Correction: I don’t merely want to go to school here, I want to live in this place. I look across to my apartment building a few hundred feet away and think well, at least I got close.

David Burbank, Sacristan Of Saints Peter And Paul Church, Pulls The Strings

Finally we make our way to the original church bell, housed not in the tower as you might imagine, but in a room at the rear of the church. It has since been replaced with a computer and speakers, but the old bell remains, engraved with the date it was cast: 1906. The clapper inside the bell (also called a uvula, like that little piece of skin hanging from the back of your throat) is deeply worn, misshapen from decades of use. David grabs the rope and gives it a healthy pull, and the air around us reverberates with the bell’s booming report. He turns to us with a smile. “I’m gonna get phone calls about this.”

This article is part of a series examining the fascinating people and places that make up the rich history of North Beach and The Barbary Coast. Visit us again soon for more.

The Sydney Ducks: California's First Street Gang

Our charming northeastern quadrant of San Francisco has borne more than one name since the first European settlers decided to build on these strange and beautiful hills. Today’s strip clubs on Broadway owe their lusty lineage to the Barbary Coast, which was centered on now-genteel Pacific Street; for a while we went by Little City (or Little Italy, if you were looking at a tourist guide). Of course, these days we like to call ourselves North Beach. Of all the labels this patch of land has worn over the years, however, Sydney-Town was the first.

Centered at the base of Telegraph Hill where Broadway met the waterfront (Battery Street at that time), Sydney-Town was loosely policed by The Sydney Ducks (also called the Sydney Coves), a gang of British laborers and prison escapees who made their way to San Francisco from Australia in the mid-19th century (Ducks, because the marshy waterfront was a magnet for seabirds). A small, lawless enclave, Sydney-Town catered to the fringes of a fringe society. In the anarchic maelstrom that was Gold Rush San Francisco, this neighborhood somehow managed to distinguish itself as the most debauched, vice-ridden locale of them all. A magnet for broken gamblers, drug users, petty thieves and low-level prostitutes, for over a decade Sydney-Town was San Francisco’s dark, wicked center, a repository for all things dissolute and degenerate.

A View Of North Beach From Atop Telegraph Hill, ca 1856

The streets crawled with ‘crimps,’ or bandits who specialized in drugging and kidnapping men who were then sold into forced labor on ships. Men were “Shanghaied” this way on a daily basis, and it was such a profitable enterprise that some Sydney-Town bars reportedly had trap doors built into their floors for the purpose, and it’s said that some of crimps made up to $10,000 a year in the trade, nearly $300,000 in today’s dollars. It’s difficult to imagine the shock Shanghaied men felt when they awoke in chains on slave ships bound for the Far East. The next time you complain about a hangover, just remember these guys.

Despite the dangers of the neighborhood, business was brisk, and entertainment rife: most venues had no posted closing time, and within a couple of blocks you could drink, gamble, smoke opium or rent the company of a female of nearly any race or age. The truly discerning could also enlist the services of one Dirty Tom McAlear (AKA The Geek). A regular customer at the Goat & Compass, Sydney-Town’s grimiest bar, Tom was filthy and offensive in every way, and possessed of a distressingly marketable skill: for a nickel, Dirty Tom would eat anything–and that means anything–you put in front of him. Ew. The Boar’s Head, another popular “groggery,” took its name from their unusual stage show: a sexual exhibition featuring a woman and a wild boar.

The first street gang in California history, the Sydney Ducks were criminals of the lowest order, and the undisputed lords of their derelict domain. Resourceful to a fault, they ran what would be called a protection racket today, threatening to burn the businesses of those who refused to pay. Once they had collected all they could, they would wait until the wind was blowing away from the waterfront, then set fire to the city, and proceed to loot the local properties and warehouses. Naturally, the locals always had a wary eye out for the Ducks, and adopted a phrase to use when the gang was on the prowl: “the Sydney Ducks are cackling in the pond.”

When one of the Ducks' fires, set on Christmas Eve in 1849, devastated the heart of the city, it prompted the formation of San Francisco’s first Committee of Vigilance. A quasi-legal group of businesspeople and prominent citizens who assembled to make arrests, conduct trials and even execute criminals that seemed beyond the reach of the police and City Hall, the Committee was formed to bring order to a city whose rapid growth had made it nearly ungovernable (in 1851, San Francisco had a police force of only a dozen men, in a city of nearly 25,000).

Once the vigilantes had set their sites on the Ducks, they were not to be deterred. The committee convened on the 9th of June, 1851, and the very next day ‘tried' and hung John Jenkins, a Sydney native accused of stealing a safe from a local shipping office. James Stuart, also from Sydney, was executed for murder scarcely a month later. All told, four Sydney Ducks were killed by the vigilantes, prompting scores of rattled Aussies to pick up and leave town. After ten years, the Sydney Ducks stranglehold on the neighborhood had been broken–but the lawless character of the neighborhood persisted. The center of the action shifted a block south to Pacific Avenue, and became known as The Barbary Coast.

The last mention of the Ducks in the historical record is true to their larcenous character: on December 19, 1854, several members of the gang were involved in the famous Jonathan R. Davis fight, in which they attacked Davis, an Army Captain and veteran of the Mexican-American war, and two of his traveling companions. Like their run in San Francisco, it didn’t end well for the Ducks: Captain Davis singlehandedly killed eleven of the attackers, seven with his revolvers and four with his Bowie knife, earning a reputation as one of the most wily gunslingers in California history.

This article is part of a series examining the fascinating people and places that make up the rich history of North Beach and The Barbary Coast. Visit us again soon for more.

Talkin' Boont: Lingo and Beer in The Andersen Valley

At our recent Talk Nerdy To Me tasting event on August 2nd, we had the pleasure of hosting Andersen Valley Brewing Company’s Todd Heppe. Once again, it was a great night, and Todd did an amazing job, He held court for well over an hour, talking knowledgeably on every aspect of the brewery’s methods and unique products.

Of course, Todd was also good enough to pour some delicious treats for our lucky guests. Particularly interesting was an early entrant, the Briney Melon Gose. I typically don’t like sour beers, but the gose was a pleasant and refreshing surprise. It's easily the best sour beer I’ve had, with subtle watermelon notes balanced by just a touch of sea salt. Definitely worth a try, especially on a warm Indian Summer afternoon. My favorite of the bunch, though, was the Wild Turkey Bourbon Barrel Stout. With hints of bourbon rounding out intense but balanced flavors of chocolate and coffee, this is arguably the best stout coming out of California right now. As of press time we’ve got both on tap, so step lively!

Anderson Valley Brewing Company's Briney Melon Gose

Considered to be one of the pioneers of the American craft beer movement, Andersen Valley Brewing has been turning out remarkable artisanal beers and ales for nearly 30 years. They still operate in Boonville, California, out of a three-story Bavarian-style brewhouse they built back in 1998. They’ve seen their share of change in Boonville over the decades, but odd things still persist.

The most fascinating one Todd mentioned had nothing to do with brewing, and has had us scratching our heads in wonder ever since: Boontling is a language with over 1,000 unique words and phrases that came into use among Boonville locals in the late 19th century. It’s derived primarily from English, incorporating elements of Scottish Gaelic, Irish, Spanish and Pomoan (a family of Native American languages originating in Northern California). It is said to have been invented originally by Boonville children so that they could talk behind their parents’ and teachers’ backs, and to have grown in use as they matured into adults.

Andersen Valley Brewing Company's Brewhouse in Boonville, California

Boontling gained national attention in the mid-1970s when Boonville native and boontling speaker Bobby “Chipmunk” Glover was a regular guest on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show. Unfortunately, because most of the dialect’s native speakers are now elderly, its use has declined sharply in recent years. It is estimated that less than 100 people speak it today.

The language has an irresistible charm: Boont means Boonville, and in the verb form means to speak boontling. Anyone not from Boont is a brightlighter, and if you look like you’ve got some money, you’re high-pockety. When visiting Boonville, be careful not to drink too much blue grass (whiskey), or you might end up with a case of fiddlers – their cheerful term for delirium tremens. Speaking of such things, eesole is the Boont word for an undesirable character. I’m pretty sure that one’s from the English.

My personal favorite: one of the most widely used words in the dialect, bahl is the Boont term for good; naturally, the word for a very attractive female is bahlness. Lest you think this betrays a romantic streak in the Boont character, I’ll let you go ahead and look up hog rings and mouse ear for yourself.

Speaking of which, you'll find a lengthy glossary of Boontling words and phrases at the Wikipedia entry (trust me, it’s more than worth a look).

Remember, Talk Nerdy To Me happens on the first Tuesday of every month at 7:00pm. We've got some terrific stuff lined up, and it's bound to be bahl hornin! (that's Boont for good drinking - better study up). We look forward to seeing you here! Meanwhile, make sure to bookmark us at www.thebellecora.com, and come back soon to find out about other cool upcoming events.

Cheers!

Vagabonds, Lunatics And Scoundrels in San Francisco History, Part 2

San Francisco loves all of its children – especially the eccentrics. To speak of our city without mention of the confidence men, embezzlers, reconstructed losers and spit-shined derelicts that populate its history is to somehow miss the point of why San Francisco is so special. Our blessed burg has always been a refuge for America’s oddballs and outcasts. San Francisco is the terminus of their inexorable trip westward, their last stop before deep water – and fittingly, our nation’s bellwether of the bizarre.

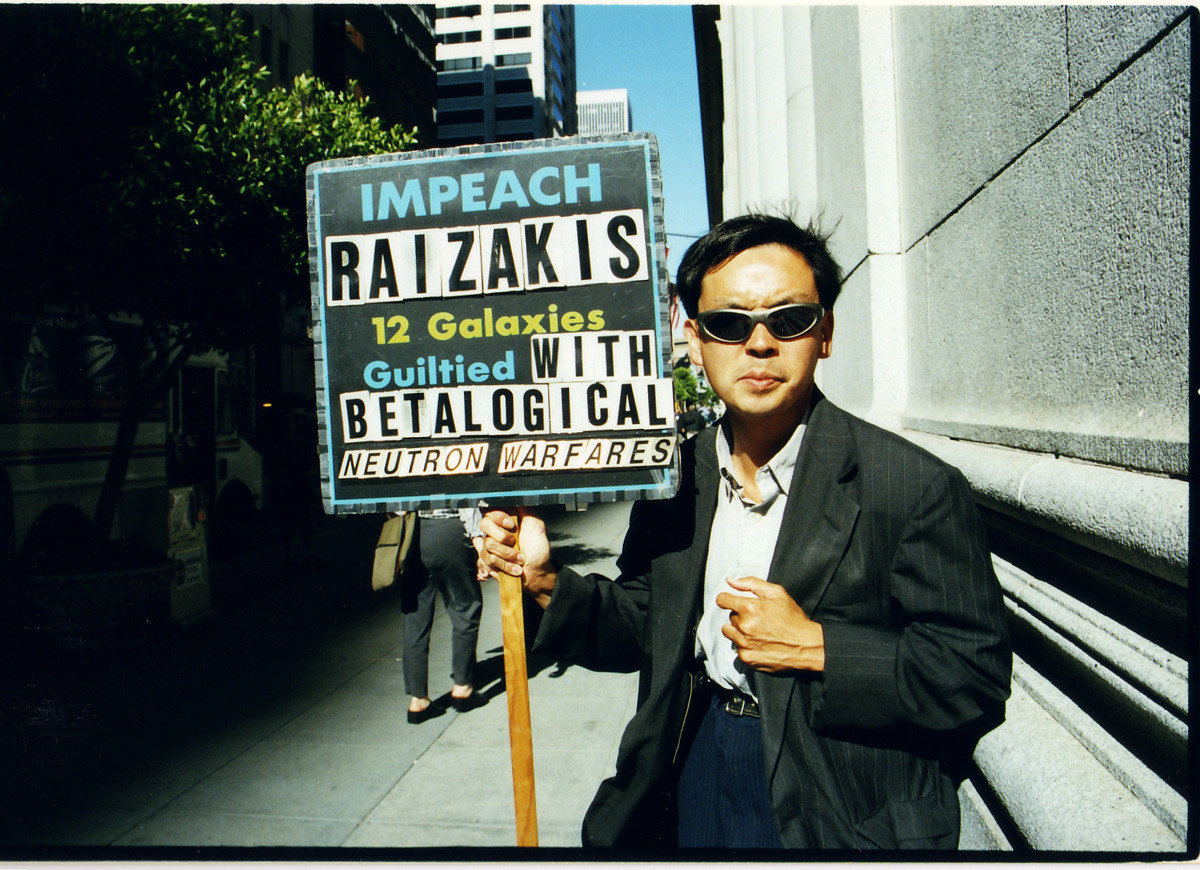

Market Street, San Francisco’s diagonal backbone, has long been a magnet for the aggressively strange. A common sight on Market, the celebrated Mr. Chu is one of the most doggedly persistent ‘demonstrators’ in San Francisco history. Hoisting his trademark hand-lettered sign, since 1999 Frank Chu has been campaigning for the impeachment of various American presidents, all of whom he claims conspire with aliens of the “12 galaxies” to secretly film him against his will. According to Chu, this stealth footage has been broadcast throughout the universe, making him into an intergalactic film and television star; accordingly, he and his family are owed billions of dollars in unpaid royalties.

Frank Chu at work in the Financial District

His colorful block-lettered signs are instantly recognizable and almost entirely unintelligible, and Chu reserves the back for ad space for local businesses. His rate: $100 a week. At one point Mr. Chu inspired a bar, where he was invited to give rambling readings (the 12 Galaxies on Mission Street, somehow closed now). The next time you are down on Market, keep an eye out for the guy in the wraparound sunglasses with the sign full of gibberish – Mr. Chu is still at it today.

A quintessential San Francisco eccentric, Anton LaVey was an author, musician and sometimes circus performer; he was also the founder and High Priest of San Francisco’s Church of Satan. Referred to in the press as “The Black Pope” and “the evilest man in the world,” LaVey founded his Satanic Church in San Francisco in 1966, attracting a coterie of prominent followers. Services were held at “The Black House,” his tiny Victorian home in the Richmond District, which he had painted jet black. A timely combination of sexual libertinism, atheism and a soupçon of show business, LaVey’s Satanism was at its core a rejection of Christianity and its values, and incorporated ideas from Nietzsche, Ayn Rand and others.

Anton LaVey with a friend

Dismissed by some as a mere publicity hound, LaVey was apparently quite serious about his church. His Satanic Bible, which Richard Metzger described as "a razor-sharp, no-bullshit primer in natural and supernatural law,” has sold over a million copies worldwide. He baptized his daughter Zeena at the Black House in 1967, performing the service above the back of a nude woman as an altar – and garnering worldwide attention.

LaVey expired of a heart attack in 1997, just a few days shy of Halloween. His church continues to this day, although it has relocated to – where else? – Hell’s Kitchen in New York City.

Perhaps as unhinged a barrister as the California court system has ever seen, David Terry was a Kentucky-born lawyer who came to California during the Gold Rush. Elected to the State Supreme Court in 1855, Terry had a violent temper, and was known to brandish a huge Bowie knife which he routinely carried in the courtroom. In 1856, the state of California declared San Francisco to be a city in insurrection; Terry was sent by the governor to settle the dispute brewing between the Second Committee of Vigilance and the hopelessly corrupt San Francisco police force. Soon after his arrival in the city, the volatile jurist was involved in an altercation in which he stabbed a protesting vigilante. Some accounts say Terry was kidnapped by the vigilantes and fought back; some claim he stabbed the vigilante in a street fight. In any event, Terry spent a few days in a cell at Fort Gunnybags, contemplating the prospect of being hanged.

The irascible David Terry

The victim survived, however, and Terry was freed, going on to run for reelection in 1859. Upon his defeat, the judge blamed his loss on California Senator David Broderick (actually a good friend of Terry’s). The bad blood eventually became so extreme between the two men that they agreed to a duel, meeting at a spot just outside San Francisco city limits; Terry outdrew the senator, shooting him dead. Though acquitted of murder, Terry left California, his political career over. He met his own death in 1889 after he attacked US Supreme Court Justice Stephen J. Field, who had ruled against Terry in his divorce proceedings. The bodyguard who shot him had been hired expressly for the purpose of protecting Field from David Terry.

In 1850, a decade before the Barbary Coast had taken its name, the south slope of Telegraph Hill was home to what may have been the nastiest, most vice-ridden neighborhood in United States history: Sydney Town. Founded by the Sydney Ducks, a gang of British prison escapees who made their way here from the penal colonies in Australia, Sydney Town was a lawless zone catering to low-level gamblers, con men, whores and opium addicts. Their mascot was a shambling wreck of a man named Dirty Tom Mc Alear, lowliest of the regulars at Sydney Town’s most desperate dive, the Goat & Compass. Filthy, malodorous and perpetually drunk, Dirty Tom (or The Geek, as some knew him) had a singular talent: for just a nickel, he would eat anything you put in front of him. Garbage, small animals, insects, feces - it didn’t matter to Dirty Tom. When you look up the word Omnivore, there truly ought to be a picture of Tom Mc Alear.

Arrested in one of the periodic purges of the crime-plagued neighborhood (the charge: making “a beast of himself”), Mc Alear claimed he hadn’t been sober for seven years, nor taken a bath since leaving England some fifteen years earlier. There is no record of Tom’s later life, though we’re guessing it wasn’t pretty. Meanwhile, the Sydney Ducks eventually had their comeuppance; we’ll return to that story in a later post.

This article is one in a series exploring the fascinating people and places that make up the rich history of North Beach and the Barbary Coast. Visit us again soon, and to see more examples of good content, visit joecontent.net.

Carol Doda: North Beach's Most Famous Daughter

In June of 1964, San Francisco was a play between acts. The Summer of Love had yet to descend upon our fair city; Kerouac, Ginsberg and the beats had already departed. Something was in the air, an unease deepened by the impending arrival of the Republican National Convention at Cow Palace in July. Before 1964, there had been only one Republican convention on the West Coast, and some took this as a sign that the party was gaining power here. The future of the city was anyone’s bet.

Carol Doda was born on August 29, 1937, in Solano County, California. Her parents divorced when Carol was three, and details of her early life are scarce, but she grew up in Vallejo, supporting herself from the age of 14 as a secretary and cocktail waitress. Arriving in San Francisco in 1963 at the age of 26, Carol began attending the San Francisco Art Institute; to pay her bills, she began working as an exotic dancer at the Condor Club on North Beach’s lively Broadway.

Her stage entrance at the Condor couldn’t have been more dramatic: a white grand piano would slowly descend from the ceiling, and atop would be the lovely, platinum blonde Carol, gyrating like a land-bound mermaid. The music was rock n’ roll, and she liked to dance the Swim, mixing it up with a bit of the Frug and Watusi. She absolutely loved it. “The minute I knew I existed in life was the night I started the Condor thing,” Carol would say later. “The only thing that mattered to me was entertaining people.”

The lovely Carol Doda in an undated photo

On the night of June 19, 1964, with the encouragement of the Condor’s publicist, Carol took the stage in a topless “monokini” swimsuit. The act was an astonishing success, and within months every club on Broadway was topless. From there, the trend quickly spread across the country. From the Condor Club on the corner of Broadway and Columbus, Carol Doda had fired the opening salvo of the sexual revolution.

Carol was a very smart young woman, and she knew a good thing when she saw one. As the crowds grew, she quickly moved to capitalize on her success, becoming one of the first entertainers to have her breasts surgically enhanced. She took 44 separate shots of silicone, increasing her bust size from 34B to a bounteous 44D. That’s a massive dose of silicone (the procedure has since been banned), but Carol would never show any ill effects. Her bust was later to be insured by Lloyd’s of London for $1.5 million.

Carol would do 12 shows a night at the Condor, performing for thousands of people a week and earning about $4,000 a week in today’s dollars. On September 3, 1969, she began performing bottomless, sparking another national trend. Carol continued to perform fully nude at the Condor until 1972, when California passed a law prohibiting fully nude dancing in bars.

Along with the Condor’s owner Gino Del Prete, Carol was arrested in 1965 on obscenity charges, but the two were quickly cleared of any wrongdoing. In 1969, Carol was called as a witness in another trial of two nude dancers arrested in Orangevale, California. Presided over by Judge Earl Warren, Jr (son of former California Governor and U.S Chief Justice Earl Warren), it was a bizarre trial during which the judge moved court proceedings three times. First, to the scene of the alleged crime – the Pink Pussy Kat Bar – where defendant Marie Haines danced for him and the jury wearing nothing but a pair of golden slippers (the jury was made up of 10 men and 2 women, in case you were wondering). Then he took the court to another bistro, where Carol performed her signature act for the same audience (the district attorney opposed asking Carol to perform, but was overruled by a resolute Warren). The judge wrapped up the tour by bringing the jury to view the Swedish erotic film“I Am Curious, Yellow” at a local theater, “to provide context.”

The dancers were acquitted. After the trial, Judge Warren told reporters “we’d like to salute the American judicial system, which believes in getting all the evidence in.”

At the height of her fame, Carol was internationally known. She appeared in Bob Rafelson’s 1968 film “Head,” featuring The Monkees, and was reportedly the inspiration for Russ Meyer’s “Mondo Topless.” By 1982 she was again at the Condor performing three shows a night. Carol had started working more on her singing at this point, and for several years in the eighties she fronted local band the Lucky Stiffs, playing clubs around the Bay Area. She retired from stripping in 1985 at the age of 48, and later opened her eponymous lingerie boutique on Union Street in the Marina District.

Carol poses on Broadway in front of the Condor Club, 1982

Though she closed up shop in 2005, Carol never stopped singing, and lots of North Beachers know her from her performances here in the neighborhood at Tupelo, Amante and long-gone Enrico’s, often with bandmate Dick Winn at her side. Carol was a regular presence in North Beach, a walking piece of history, an attachment to our collective past as reassuring as the Moon overhead. As night owls will attest, she was a wee hours irregular across the street at Gino & Carlo, where she was afforded a level of respect normally associated with visiting royalty. If you were lucky enough to talk with Carol at the bar, you were in for a treat. She was quick-witted, kind, funny and sweet. Also, Carol was a very good listener – and that’s a remarkable impression to come away with at 1:30 in the morning.

Teague Kernan remembers her in much the same way. Co-proprietor of Belle Cora (and owner of Tupelo just around the corner), Kernan is a North Beach night owl who over the years has haunted many of the same barrooms as Carol. Over the years he got to know her well, and considered her a friend. “I truly loved her, as a person and an entertainer. She was an icon, but I never saw her that way. She was reserved in a way that I understood,” he said of Carol.

When she passed away of kidney failure at 78 in November of last year, Teague and his team at Tupelo hosted a moving, bittersweet memorial. Carol’s final audience, the crowd told one another old stories, looked at stunning photos of Carol through the years, and eventually spilled onto Grant Avenue – just steps away from where Carol had made history 51 years earlier. North Beach had lost its most famous daughter, and America a big piece of its history. Carol Doda was a provocateur, a lady and a true San Francisco original, and we won’t see her equal anytime soon.

At a performance in 2009, when asked if she would ever give up the stage, Carol was characteristically quick to reply: “The only way I’ll stop performing is when I can’t walk anymore, honey.”

We’ll all miss you, beautiful.

This is the third in a series of articles examining the fascinating people and places that make up the rich history of North Beach and The Barbary Coast.

Vagabonds, Lunatics and Scoundrels in San Francisco History, Part 1

One morning in the Spring of 1841, Pennsylvania businessman Paul Geddes was on his way to the bank to deposit $7,000 for his employers. That was a considerable sum in 1841, so he was clearly a trusted employee, but Geddes must have been feeling lucky that day; he decided to stop and play a few hands of poker on the way downtown. In the time it takes a civilized man to have lunch, he managed to lose every dime of the deposit. Unable to face his employers and the authorities, Geddes left town, abandoning his wife and five children.

Heading west, he reinvented himself as Talbot Green, landing in San Francisco after a rugged trek across the Sierras. Here in California he embarked on a second successful career, rising to become U.S. customs collector and serve on the city’s town council. Talbot Green was highly regarded in San Francisco, so much so that he was on the verge of running for mayor when he was recognized at a charity ball by a young woman from his previous life. The ruse unravelled, and his past was exposed by a local muckraker. Though he maintained his innocence, Green was forced to leave town in disgrace, and eventually returned to his family in Pennsylvania. Today, all that’s left of Talbot Green in San Francisco is the street named for him in the 1849 survey: Green Street.

To be sure, Talbot Green was a world-class scalawag, and he is only one among many in our city’s history. There is no shortage of eccentric, larcenous, and just plain odd characters in San Francisco’s colorful past.

Consider Black Bart. One of the most celebrated bandits in California history, Charles Bowles was a prospector and bank teller who served as a Union sergeant in the Civil War. After a series of financial reversals (including a run-in with Wells Fargo agents that evidently stuck in his craw), Bowles career took a sharp detour. Adopting the nickname “Black Bart,” he began periodically sticking up Wells Fargo stagecoaches in California, reportedly with an unloaded shotgun. History would have likely forgotten Bowles if he hadn’t come up with his sobriquet, along with a gimmick to taunt the hated Wells Fargo: at the scene of at least two of his robberies, he left behind a poem. Signed “Black Bart the PO8,” here’s his first:

I’ve labored long and hard for bread,

For honor and for riches,

But on my corns too long you’ve tread,

You fine-haired sons of bitches.

Well-dressed and unerringly polite, Bowles struck at least 28 times between 1875 and 1883, and made a very good living at his new trade; most evenings he could be found quietly sipping brandy in the corner of Martin and Horton’s Saloon on Montgomery Street. But he eventually paid for his crimes: wounded in the hand during his final robbery, Bowles was later arrested and served seven years in San Quentin. Wells Fargo only pressed charges for the last robbery, and upon Bowles’ release there were rumors that the bank had paid him off to keep him from hijacking their stagecoaches. Wells Fargo denied the charge.

Black Bart

Surrounded by reporters as he exited prison, the bandit was asked if he was going to rob anymore stagecoaches. “No, gentlemen,” he told them, “I’m through with crime.” When then asked if he would write more poetry, he laughed and said, “Now, didn’t you hear me say that I am through with crime?”